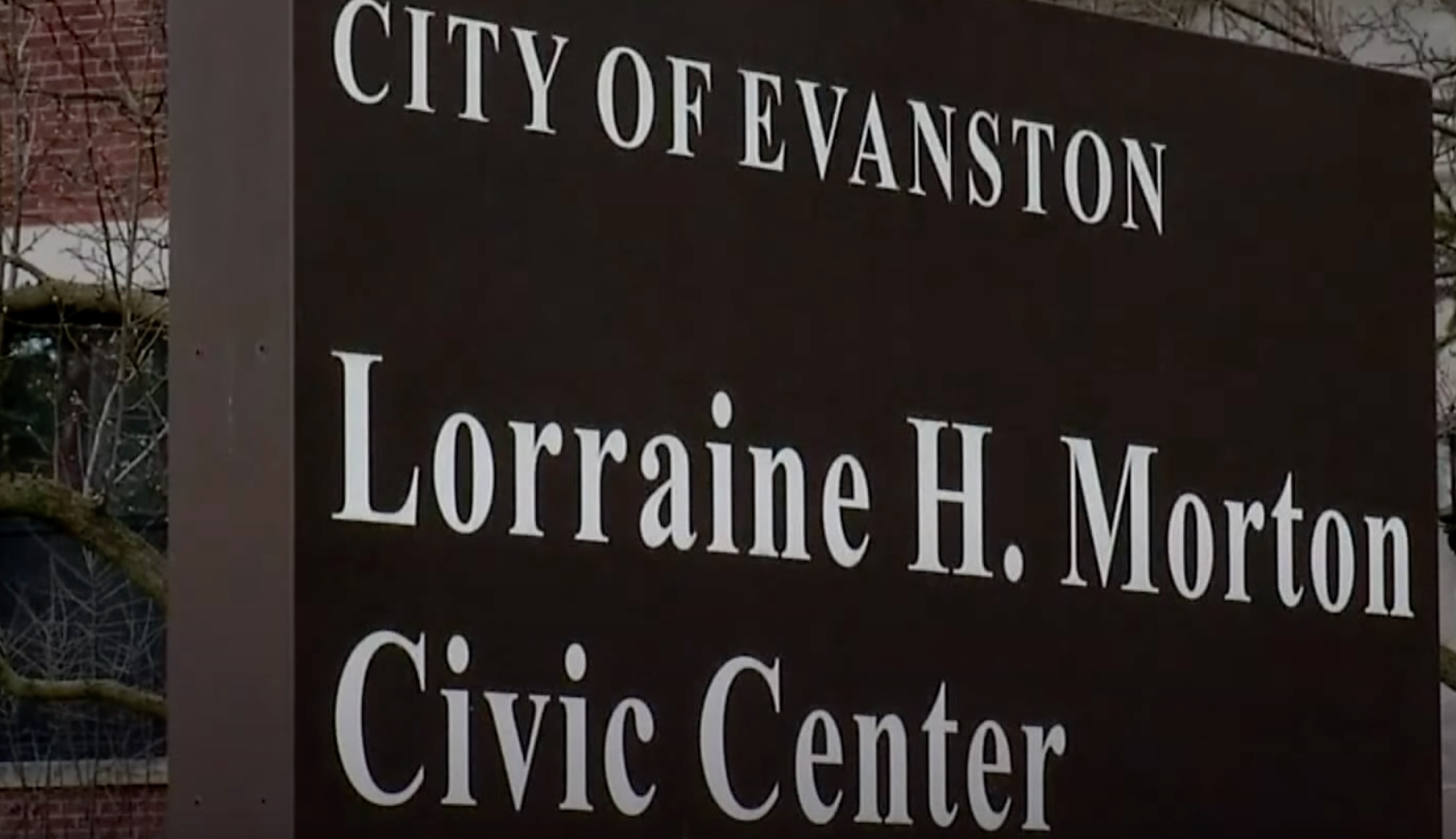

Evanston, a suburb of Chicago, made history by implementing the nation’s first government-funded reparations program for Black Americans.

The program has distributed nearly $5 million to 193 Black residents in the town.

A conservative advocacy group has filed a class-action lawsuit challenging the program, claiming it discriminates against non-Black residents in the suburb.

This lawsuit is part of a series of legal actions influenced by the Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling against affirmative action in college admissions.

Conservative organizations have now expanded their efforts to target diversity programs, including fellowships, and are pushing to open up the federal Minority Business Development Agency to White business owners.

“This program redistributes tax dollars based on race,” said Tom Fitton, president of Judicial Watch, the group that filed the lawsuit against Evanston. “That’s just a brazen violation of the law.”

Cynthia Vargas, the communications and engagement manager for the city of Evanston, stated that the city “will vehemently defend” its reparations program. She refrained from discussing the details of the lawsuit filed in federal court at the close of May.

Advocates for reparations express concerns that this legal action could disrupt a broader nationwide initiative aimed at providing compensation to Black Americans for the enduring consequences of centuries of discrimination.

Jason Schwartz is a lawyer with Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher representing the Fearless Fund, a venture capital firm that provides grants to Black female entrepreneurs, against a similar lawsuit.

Schwartz said “This lawsuit is part of a larger movement to challenge race-conscious programs in all aspects of society.”

A panel from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit issued a ruling on Monday that temporarily halts an Atlanta-based venture capital firm from providing grants exclusively to businesses owned by Black women. The decision was made on the grounds that such targeted grants could potentially discriminate against business owners of other racial backgrounds.

In recent times, over a dozen states and cities, such as New York and Boston, have initiated studies on the feasibility of implementing reparations for their Black residents. Lawmakers in California are also deliberating on a proposal to establish a state agency responsible for overseeing potential reparations programs.

Kamilah Moore, chair of California’s Reparations Task Force, highlighted that attention has now shifted back to Evanston, the city that played a key role in kickstarting the national reparations movement.

“What happens in this case will definitely have an effect on what kind of programs we see rolling out” in other communities, Moore said.

Judicial Watch filed a lawsuit on behalf of six non-Black residents of the city, contending that the program’s requirement for eligibility based on race violates the 14th Amendment. This amendment was designed to protect the rights of millions of Black Americans who were once enslaved after the Civil War. In recent times, conservative legal professionals and judges have invoked the 14th Amendment to challenge programs that they believe unfairly benefit Black Americans and other minority groups.

Last June, the argument gained traction when the conservative majority in the Supreme Court invalidated affirmative action in college admissions. Horace Cooper, the former constitutional law professor and chairman of Project 21, expressed that the court’s ruling effectively barred race-based reparations programs. Project 21 advocates for conservative strategies to address issues affecting Black Americans.

Cooper emphasized that the ruling clarified that the government is prohibited from both discriminating against individuals based on their race and from providing benefits solely on the basis of race.

“You can have a program that only gives money to people under 30, or you can have a program that only gives money to people in wheelchairs,” he said. “But when you use race, the court has looked on that with a great deal of suspicion.”

Critics of reparations have contended that it is challenging to fairly compensate the descendants of enslaved individuals and that it is unjust to expect individuals with no ties to slavery or involvement in racist policies to bear the responsibility for the mistakes of the past.

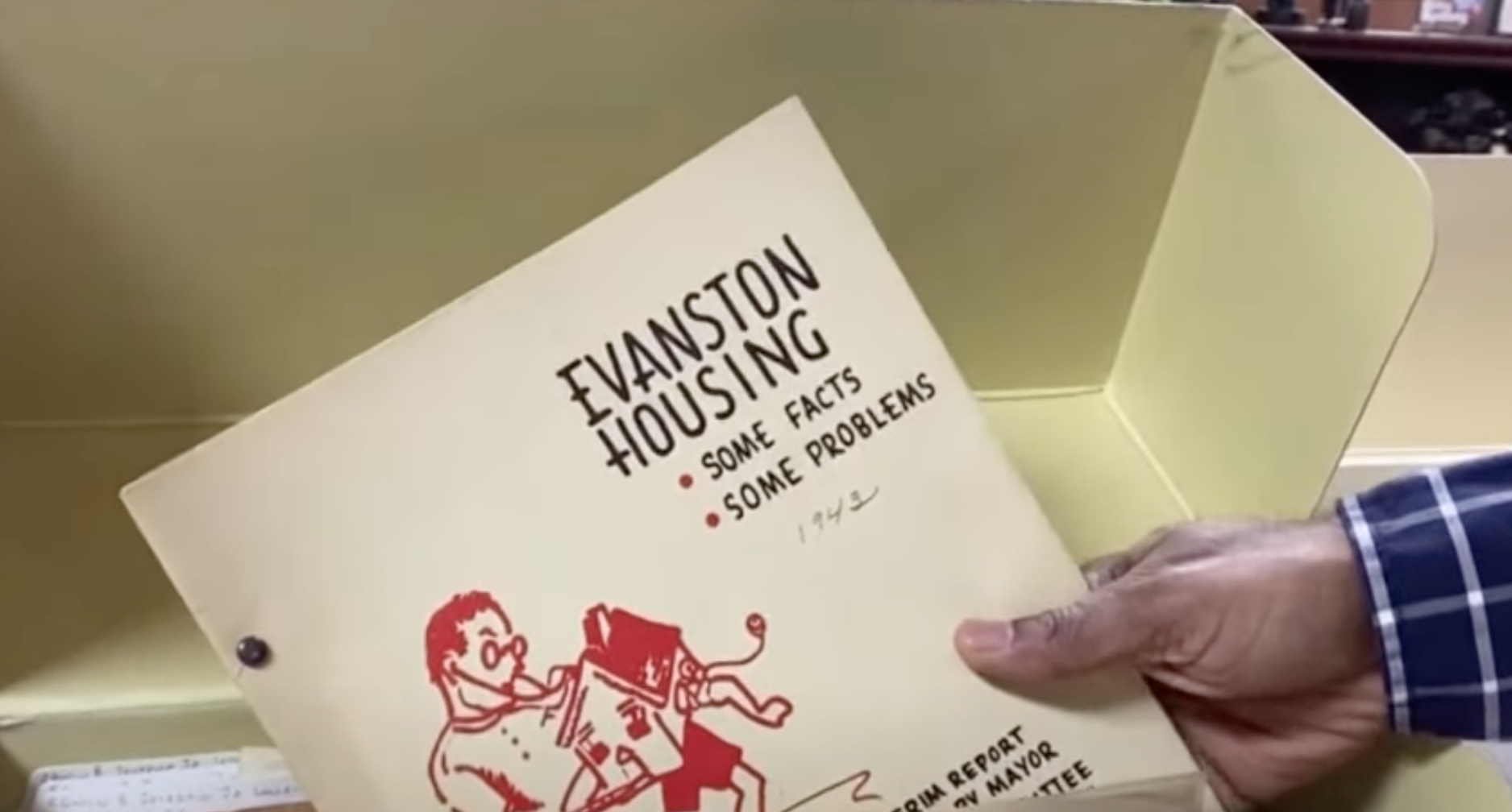

Evanston’s $20 million reparations program is available to Black individuals who resided in the city or whose direct ancestors lived there from 1919 to 1969. During this period, Evanston authorities acknowledged implementing discriminatory housing practices that hindered Black residents from accumulating wealth.

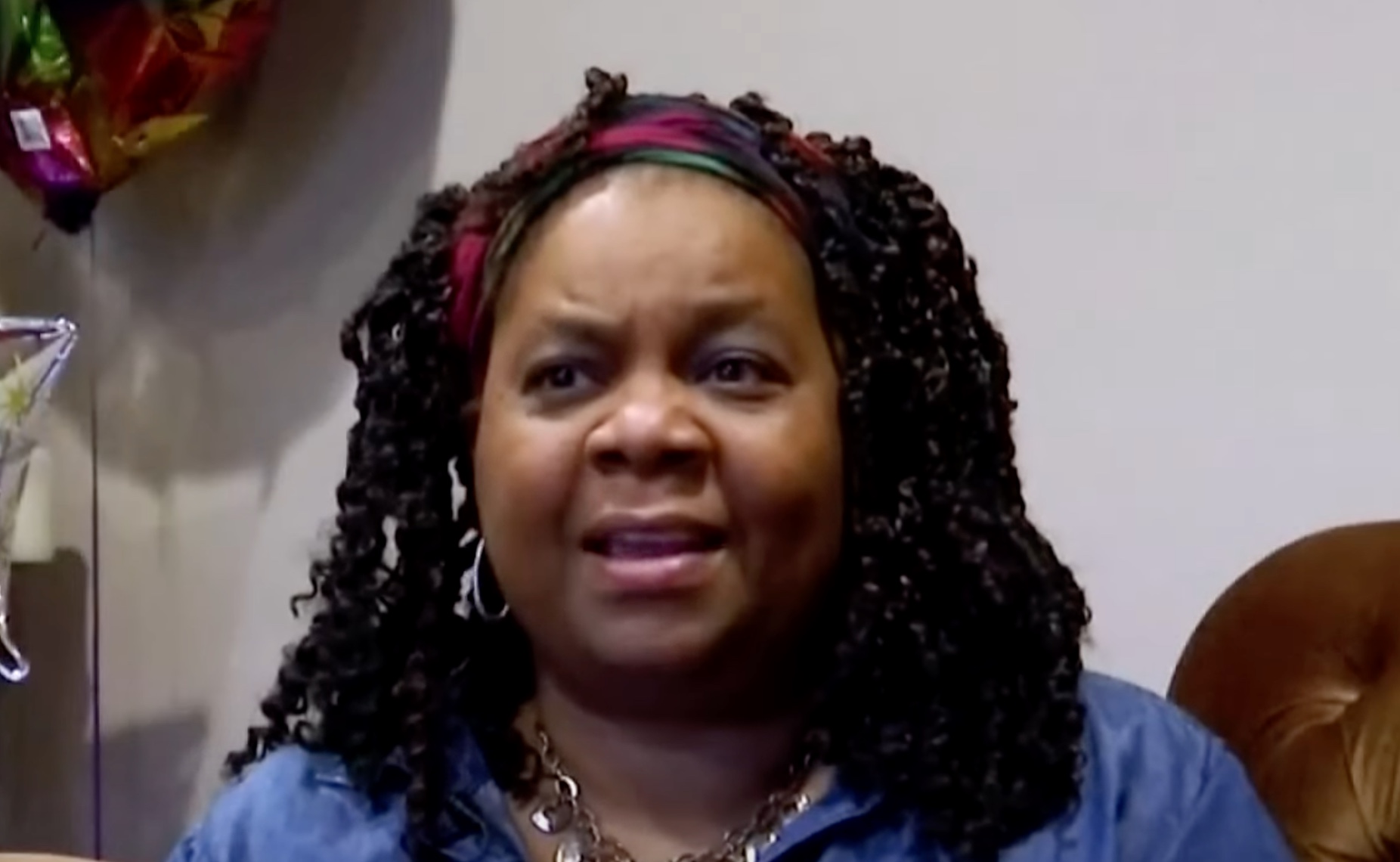

Initially, eligible participants in the reparations initiative received a $25,000 grant for home purchase or repairs. However, the program was later expanded to offer a $25,000 cash payment alternative. Despite these efforts, there are still hundreds of individuals on the waiting list.

Robin Rue Simmons, a former city alderman who advocated for reparations, has traveled across the country to promote Evanston’s program and collaborated with activists in numerous cities to replicate similar initiatives. The story of this endeavor is the focus of a documentary titled “The Big Payback,” which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Fitton, the president of Judicial Watch, emphasized that their lawsuit aims to uphold the principles of the United States’ “colorblind Constitution.”

The lawsuit argues that Evanston’s program is unfair to the city’s non-Black residents and should only benefit individuals who can demonstrate they have faced discrimination within the city. In Evanston, approximately 60% of residents are White, 17% are Black, and Hispanic and Asian residents each comprise slightly less than 10% of the population.

Reparations advocates in various regions have foreseen these legal disputes. For instance, when Providence, Rhode Island, introduced its $10 million reparations program in 2022, city officials designed it in a way to minimize potential legal challenges. While Black and Native American residents automatically qualify, the city also implemented income criteria that could encompass around half of its White residents.

The California Reparations Task Force put forward a proposal last year for up to $800 billion in reparations, suggesting that it be allocated exclusively to the descendants of both free and enslaved Black individuals who resided in the United States before 1900. Advocates of this lineage-based strategy argue that it would potentially withstand legal scrutiny by excluding Black residents whose families immigrated to the U.S. more recently.

“The Supreme Court affirmative action decision came down the same exact day of the task force’s last hearing,” said Moore, who chaired the California panel. “I said at that hearing, this would have been a somber day if we had used a race-based eligibility, but with our approach, I really do believe that we live to fight another day.”